Highlights of the SoilFeeders Project (Sept 2022 - May 2023) From Food Waste to Regenerative Farming

According to the latest figures by The Environmental Protection Department (EPD) of Hong Kong, the hospitality industry produces an average of 1,095 tonnes of food waste on a daily basis. These leftovers tipped the scales as the largest municipal solid waste category.

Food waste that ends up in landfills not only takes up space but also releases methane and CO2 which are potent greenhouse gasses, and contributes to global warming. Taking action against food waste is an impactful measure we can take to address climate change.

A cross-sector collaboration pilot project called “SoilFeeders” that was funded by Zero Foodprint Asia attempted to establish a kitchen-to-farm regenerative solution to transform food waste from the F&B industry and give the nutrients back to the land to rejuvenate soil health.

Hotel-made & Locally sources Bokashi was born

Bokashi (ぼかし) originates from Japan and has been imported and sold as commercial ready-made kits. SoilFeeders experimented with locally sourced, self-reliant carrier materials such as rice bran, sawdust and coffee chaff, and a self-generated microbial starter culture (eco-enzyme) to create Bokashi from scratch.

The cross-sectoral endeavor was made possible with hospitality partner Hyatt Centric Victoria Harbour. The kitchen teams separated fruit and vegetable trimmings and a total of 1,250kg of otherwise landfill bound food waste was collected. The SoilFeeders team participated and observed the kitchen operations at the hotel. Following on from this induction training on how to best separate and collect the food waste was conducted and detailed implementation manuals were provided for the hotel kitchen staff.

Organic resource recovery at the source and in action: Fruit peel brew (ecoenzyme) from trimmings, calcium powder from cleaned/crushed eggshells and Bokashi layering with kitchen trimmings and provided microbial carrier on hotel premises.

A hygienic way to convert food waste

In many food waste recycling projects, unfavorable smell, storage space and time are always the barriers for businesses to participate. What is different about the bokashi method from the untreated food waste is that the food scraps were multilayered with Bokashi bedding and stored in air-tight containers. Key to this is that the anti-microbial Bokashi did not emit foul smell and remained hygienic, so has increased acceptance when it is recycled.

The F&B staff also agreed the process was unexpectedly simple, and it was easy to incorporate it into their kitchen routine as it only took one or two dedicated days in a month.

Safe food waste and nutrient recycling for farm

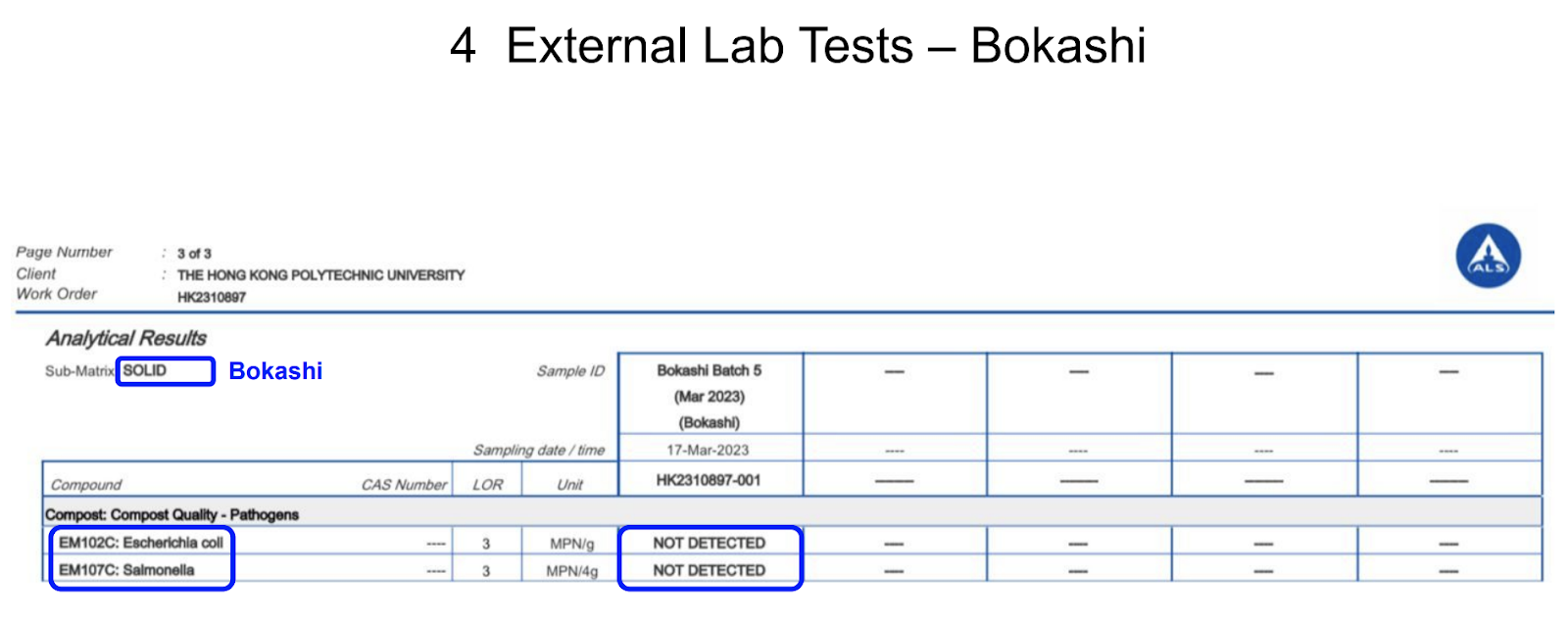

Food waste in unsorted and raw form can contain plastics or unknown pathogens, thus it might cause problems to the soil if used incorrectly. The Bokashi collected from Hyatt Centric hotel were source-separated and plastic-free. An external lab test result proved that the Bokashi made by SoilFeeders was free of two common pathogens: Escherichia coli (E.coli) and Salmonella. This aniti-microbial property of Bokashi also contributes to a more hygienic way of recycling food wastes and safe to use in food production.

The pathogen test of SoilFeeders’ Bokashi done by an external lab ALS Techichem (HK) Pty Ltd.

Increased Onsite Storability

The SoilFeeders farm team were the frontline caretakers to turn the bokashi-processed hotel food waste into a soil amendment in the farm. As the quality and maturity of the Bokashi in container drums can vary and were difficult to standardize, the farm team tried out various ways to apply and strived for a balance to not integrate in an invasive way as minimal disturbance on soil is a principle of regenerative farming. And they recommend converting the Bokashi into stabilized organic matter through thermo-composting.

Hospitality partners are mixing the Bokashi collected from the hotel with the municipal mulch and green waste into a cubic meter pile for thermocomposting.

It coincidentally eased the problem that many farmers are facing:

Composting is an implementation practice that is highly recommended for the transition to regenerative farming.It requires an ideal ratio of green materials (i.e. the nitrogen-rich source that are normally still wet and colorful such as food waste) and brown materials (i.e. the carbon source such as wood branches and brown leaves). For local context, farmers find it difficult to source clean and reliable brown materials thus take longer time to gather. Not to mention green materials tend to rot easily and are more challenging to store. Turning food waste into Bokashi form can prolong the onsite storability of green materials for years and minimize odor simultaneously.

Bokashi container drums filled with processed food waste delivered from hotel to farm and stored as materials for future thermocomposting

After this on-site trial run, the kitchen-to-farm Bokashi operation model is tested to be feasible and scalable. However, there were some challenges with factors affecting the outcomes of the trial.

Challenges and possible solutions

Crop health monitoring best to be done on sunny days: During the project, it was realized that cloudy and rainy weather made testing and monitoring challenging. Therefore it would be more appropriate for some testing such as Brix measurement to be conducted during the dryer periods such as November-February for more accurate results.

Time was the most limiting factor in the project: For effective monitoring, more time is required in the whole composting process so that its maturity can better monitor the improvement of soil health. We have observed that the germination rate of a 4-month Bokashi is less effective compared to a 6-month Bokashi, and using certain materials, like wood chips, as composting materials might take more than 6 months to mature. Alternatively, the team found that substituting wood chips with fallen leaves and agricultural wastes as brown materials speeds up the composting process. Although our study plan was forced to be cut short due to the return of farmland upon the landlord’s request, this effectively shortened the composting time and thus study time of the project outcomes. Land lease time could have been negotiated by the project team ahead of the project start date to reduce the impacts of future uncertainties like this on our projects.

Labour costs can be high: Another learning worth noting is that although the input costs of using Bokashi are low, its labor costs can be high when it comes to the application of the compost. This struggle can be loosened by the scaling up of the activity. If a unit can manage the pick-up, composting and delivery of the composts from F&B businesses to farms, the farmer’s work can be saved to focus on the agricultural production and output alone. Moreover, we have known that no-turn or static composting methods can be further explored to reduce labor costs.

It is undeniable that more research and experiments can be conducted to further explore Bokashi’s application in regenerative farming. For instance, developing the potent eco-enzyme and effective microorganism (EM) using local resources is worth the effort as it can increase the independence from external commercial products (i.e. “nutrient autonomy”), and reduce local food waste and waste materials problems at the same time. But in order to yield compost of good quality, a complete Bokashi fermentation can take as much time as composting directly on the farm.

It has also been found that liquid biofertilizers using materials like fruit peels are less nutrient dense due to the lack of quantity and diversity of active microbes. Therefore, in terms of relying on food and hospitality outlets to produce composts to raise soil fertility, whether this methodology truly justifies the emissions caused during transport, as well as the additional labor hours required from both hospitality staff and farmers, have yet to be tested. And at length, whether this activity yields more beneficial social outcomes compared to anticipated agricultural outcomes; more time is required to produce a true study of the vast range of benefits.

By diverting food waste throughout this project, we have successfully avoided up to 277 kilograms of carbon dioxide and 18 kilograms of methane emissions compared to landfilling the food waste. Diverting food waste to agricultural systems has the potential to raise soil fertility and crop productivity, but more studies are required in order to yield the most beneficial outcomes for both the hospitality sector as well as farmers. Diverting food wastes is an effective way to reduce carbon by saving them from landfills and it remains a bright solution to cut down our emissions contributing to climate change. With the abundance of nutrients within, food wastes are NEVER just trash. To make good use of them, we should continue to work to reintegrate these “wastes” back into the ecosystem regeneratively and collaboratively. However, at this moment, the scale of this pilot is not feasible to be done in a city context without the appropriate logistics, facilities and government support. It is very important, for both individuals and society, to recognize the reasons why we need food waste diversion urgently to save ourselves from the intensifying climate crisis.

Despite that, it is still of prime importance that we minimize our food waste to lessen the planet’s burden to contain our emissions. We need to act to solve the root of our problems, and this would not be possible without the involvement of everyone. Our planet is everyone’s home, and we need to act to protect it.

For more information, please check out other articles at ZFPA website and Instagram @zerofoodprint.asia. Together, let’s eat our way out of the climate crisis!