Carbon: To offset or inset?

Mandatory requirements from governments and stock exchanges to disclose carbon emissions are bearing down on corporations. But calculating and disclosing baseline data is not enough – businesses must demonstrate progress in reducing emissions and moving towards their net-zero commitments.

Carbon offsetting is commonly adopted by corporations to reduce emissions by purchasing carbon credits or paying a third party to implement carbon removal activities. On the other hand, carbon insetting requires businesses to identify ways to reduce emissions across their supply chain directly.

While it is tempting to opt for an offsetting approach and continue business as usual, shining a light on your own operations presents an opportunity to create a more resilient supply chain and generate operational savings. For example, by switching to renewable energy sources, you mitigate risks associated with fossil fuels, like unstable energy prices and further ecosystem degradation. Implementing better land management is another way to reduce emissions and create a positive impact across the value chain by improving soil health to draw down carbon and support natural materials required for production.

An example from CLP in Hong Kong

These are proven benefits of carbon inset practices, and more and more businesses are switching to this approach. Two of the world’s largest fast-moving consumer goods companies, Nestle and Unilever, are adopting more regenerative agriculture, improving soil health, and integrating trees and livestock in their farmlands to store carbon. Walmart established Project Gigaton to experiment with carbon insetting on energy, waste, packaging, nature, product use and design, and transportation. IKEA also supports and collaborates with their suppliers to reduce all parties’ carbon footprint and refuses to buy carbon credits.

Controversy around carbon offsetting

Carbon offsets can be a useful tool if they provide additional and long-lasting impact to reduce emissions, but they do not address the root cause. Time and again, carbon credit projects have been exposed as having insignificant impact at best, and at worst, causing more than harm than good.

A lack of transparency and legislation in the carbon market has led to carbon offsetting becoming an instrument for companies to make hollow claims of carbon neutrality, and for irreputable credit providers to pocket millions of dollars through failed carbon credits.

In response, the World Rainforest Movement along with other alliances has issued a press release to stop carbon offsetting schemes entirely, indicating they do harm both the environment and the frontline communities.

The Nature Conservancy, however, believes we cannot dismiss carbon offsetting and offers various use cases for companies to compensate for things that we are yet to find alternatives for, such as emissions from jet-fuels.

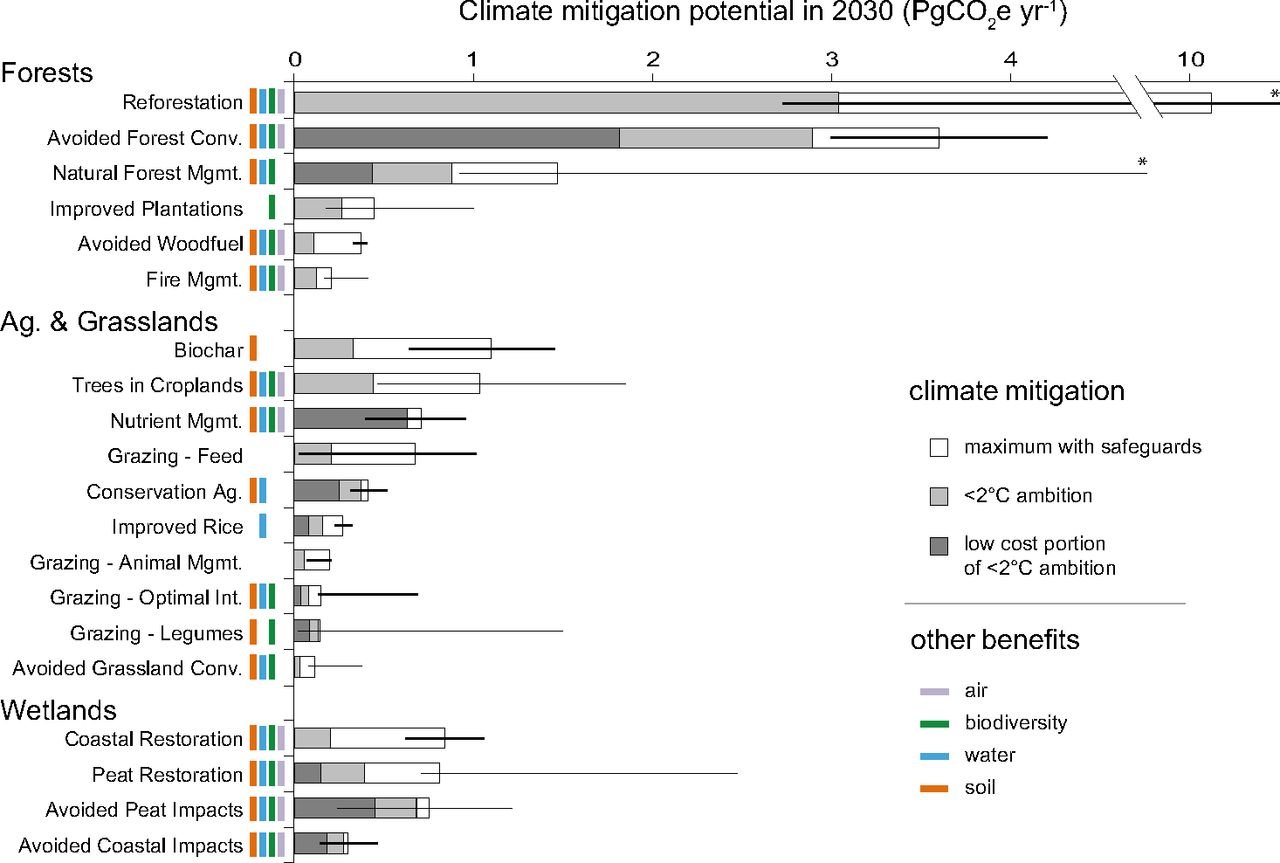

Pathways of Natural Climate Solutions; Source: Griscom, et al.

We are investigating how we can translate the impact of our regenerative rice project with Astungkara Way into valid carbon credits. By entering the carbon market, the project would receive the financial support needed to scale up regenerative rice systems in Bali, which is often the barrier for farmers wanting to make the transition.

Carbon offsetting has its place, but it will come down to a sophisticated verification process and truthful reporting by businesses.

References:

Griscom et al. (2017) Natural climate solutions. PNAS. Retrieved from: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1710465114